by Ema Katrovas

LIBRETTI

Jason Cady

Jerome A. Parker

Adrienne Danrich

Jerry Lieblich

Krista KnightMUSIC

Jason Cady

Pauline Kim Harris

Phil Kline

Matthew Welch

Aaron Siegel

Melissa Dunphy

Paul Kerekes

Clarice Assad

Miguel Frasconi

Kamala SankaramCAST

Dawn Logan: Britt HewittGloria Logan: Sishel Claverie

Carla: Eliza Bonet

Anya: Maggie Finnegan

Mac Logan: Aaron Engebreth

Ed: Joshua Conyers

Joy: Meroë Khalia Adeeb

Dr. Slade: Laura Strickling

ENSEMBLE

Maya Bennardo, Violin

Hannah Levinson, Viola

Tristan Kasten-Krause, Bass

Matthew Evans, Percussion

Karl Larson and Will Healy, PianoPRODUCTION TEAM

Director: Alison Moritz

Associate Director: Ian Silverman

Director of Photography: Eric Thomas Paton

Associate Director of Photography/ Editor: Travis Ford

Production Designer: Jean Kim

Technical Directors: Steven Brenman and Kya Naugle

Props Master: Jessica Smith

Costume Associate: Don-yá Ortiz

Projection Designer: Michael Redman

Lighting Designer: Stacey Boggs

Lighting Associate: Betsy Chester

Music Director: David Bloom

Sound Engineer: Jeff CookPremiered in Fall 2022 on All Arts. Currently available on All Arts (for US residents) and on the Opera Philadelphia Channel worldwide until October 2023

Watch trailer here.

An audio version of this article is available on the reviewer’s podcast here.

Experiments in Opera’s Everything for Dawn is an experiment in mediums: A 10-part TV show script with 15-20 minute episodes written by librettists in a writers room, each episode set to music by a different composer, acted by classically-trained singers, and filmed by a crew consisting mostly of theater creators rather than film specialists.

Of course, while Everything for Dawn pays homage to TV and opera it is actually in a different medium altogether: streaming. The project exists on and was partially funded by the streaming platforms All Arts and to a lesser extent In Series and the Opera Philadelphia Channel. Though streaming is the direct descendant of TV, it is a very different medium: First, it lends itself to solitary viewing. Second, it exists in a space where one can click away at any time. On the one hand, this has led to more creative flexibility, and some would say a TV renaissance (TV makers no longer have to “play to the middle”)[1] but on the other hand it has supercharged the science of storytelling which keeps one hooked (because viewers curate their viewing experience) which is, unfortunately, a tough space into which to release an opera. Everything for Dawn boldly confronts the question of whether opera belongs in this space at all.

Taking a page from the film and TV handbook, the creative process of the series began with a writers room which consisted of 6 librettists (Jason Cady, Jerome A. Parker, Lauren D’Errico, Adrienne Danrich, Jerry Lieblich, Krista Knight) who each wrote or co-wrote one or more episodes, but plotted the story together. By contrast, there was no composers room and not even a head composer (the way there is usually a head director for a TV show that may have a different director for each episode.) Instead, each of the ten composers (Jason Cady, Pauline Kim Harris, Phil Kline, Matthew Welch, Aaron Siegel, Melissa Dunphy, Paul Kerekes, Clarice Assad, Miguel Frasconi, Kamala Sankaram) had a different script to set to music with no limitations except the ensemble and no coordination except a couple workshops.[2]

So, what is it like to watch a streaming serial opera?

I admit that, to use a streaming-related term, I found this particular TV opera binge worthy, but perhaps not for the right reasons.

(pictured from left: Britt Hewitt, Aaron Engebreth)

Each episode starts with the image of a vintage TV corresponding to the era in which the action takes place (be it the mid 90s in episodes 1-3, early 90s in Episodes 4-7 or early 2000s in episodes 8-10). For the episodes which take place in the 90s, we zoom in to a 4:3 aspect ratio. Some of the episodes feature a family sitcom intro or, in the early-2000s episodes, hand-held exterior shots reminiscent of one of those hip Manhattan shows or of reality TV. The main difference is that the strings and piano and percussion continue relentlessly as the drama unfolds and all the characters are played by classical singers lip synching to themselves. The series doesn’t acknowledge the tropes of streaming (skip intro, binge-inducing cliff hangers) at all because it’s easier to pay homage to a medium when one is not in it, I suppose. In that sense, Everything for Dawn can best be described as a “streaming opera that pays homage to the last decades of TV.”

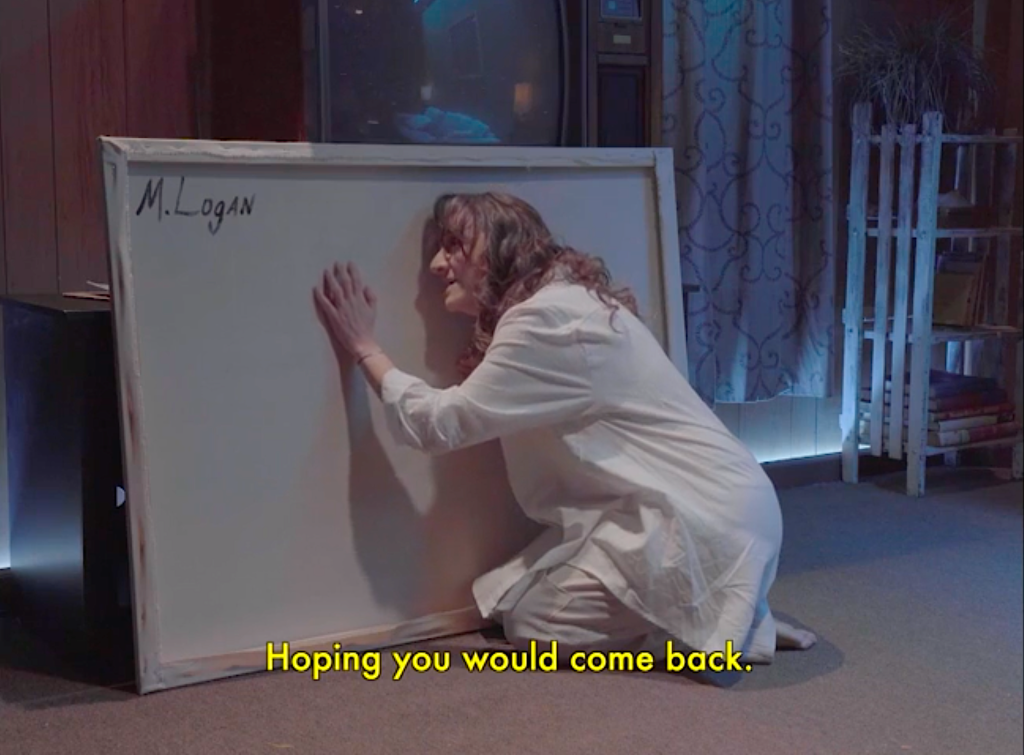

It’s the story of a working-class American family. The protagonist is the stereotypically self-absorbed teenaged Dawn (Britt Hewitt), who wishes to study visual art in college. Dawn’s mother Gloria Logan (Sishel Claverie) is a post office worker who is struggling to make ends meet while also paying in to a spiritual cult led by a charismatic guru. Dawn is upset in the first episode because her mother, in a ploy to make some extra cash, rented Dawn’s room out to a stranger, Carla (Eliza Bonet), without asking permission.[3] This new live-in turns out to be an amateur artists and her girlfriend, Anya (Maggie Finnegan), turns out to be an art curator. Thus, the crux of the story: Dawn’s father Mac Logan (Aaron Engebreth), who committed suicide a few years before the action begins, left behind some paintings he had made in his art therapy classes. His paintings have a haunting hold over everyone – in Carla’s words: “I don’t know how but he pulls me in. So personal I’m in his skin” (episode 2, libretto by Jerome A. Parker) or as Anya, the curator, puts it: “A postmodern attack blurring the lines between lavish and ordinary. Playful pastiche. Tender revelation blurring the lines between hope and desperation” (episode 3, libretto by Lauren D’Ericco). Their mystery is only deepened by the fact that we never see them. Anya wants to display Mac’s work posthumously.

(pictured: Sishel Claverie)

The answer to “What keeps viewers watching?” has become a science on streaming platforms. In the case of Everything for Dawn I can only offer you a study on a sample of one: It was the question of what was going to happen to the father’s paintings that kept me hooked. Was this a story about how a family uses the identity-narrative of a deceased family member to get rich off of his art? Would the family, on the contrary, fight against “selling out” and get embroiled with the art curator who intends to get rich off of the family’s personal tragedy? Would this be a story about how the artwork of a single person raises awareness about the issue of mental health, thus giving the family he left behind a sense of closure? Well, to use another TV trope, I won’t give away spoilers, at least for the ending.

(pictured: Maggie Finnegan)

There is something about this story that makes me think Americana, but not in the stereotypical sense of pumpkins and apple pies and baseball. I suppose part of it is that most of the characters are financially insecure yet remain dreamers: a struggling single mom who finds the money to pay into a spiritual cult, her daughter who, despite being working class, wishes to go to art school, the father who is a Vietnam vet (an American trope if there ever was one) hospitalized for his PTSD but who turns out to be a brilliant artist, though until middle age he’d never painted anything except the pinstripes on Buicks. Dawn’s father’s fellow psychiatric ward patient, Ed (Joshua Conyers), who is also a Vietnam vet, offers optimistically-delivered mad diatribes full of American tropes, from Donald Duck to conspiracy theories to his “message missiles” in the form of oranges, which are an American movie trope foreshadowing bad things to come. There’s also the conscious shout-out to how much Americans look to TV for their cultural cues, namely when Dawn says “everything’s like TV normal” which to her means ordering in pizza, watching movies, and breakfast at Denny’s before school (Episode 6, libretto by Krista Knight). The one villain of the show is the psychiatrist Dr. Slade (Laura Strikling) who is gleeful at the thought of shutting down an art therapy program led by the idealistic artist, Joy (Meroë Khalia Adeeb.) Dr. Slade and Joy are the embodiments of good and evil; while Dr. Slade actually gets a thrill from firing people, over-medicating some patients, and prematurely discharging others, Joy is an artist who believes in the power of art as therapy, and also represents the anxiety of artists confronted with justifying their own existence against a market economy, which makes her a stand in, I think, for the creators of the show (sometimes she gives in to her doubts, like when she tells herself: “…you’re useless and a fraud. And this touchy-feely painty thing’s a joke” in episode 5 with libretto by Jerry Lieblich or laments that: “The only thing worse than a starving artist is a starving art therapist” in episode 7 with libretto by Jason Cady.)

(pictured from left: Meroë Khalia Adeeb, Aaron Engebreth)

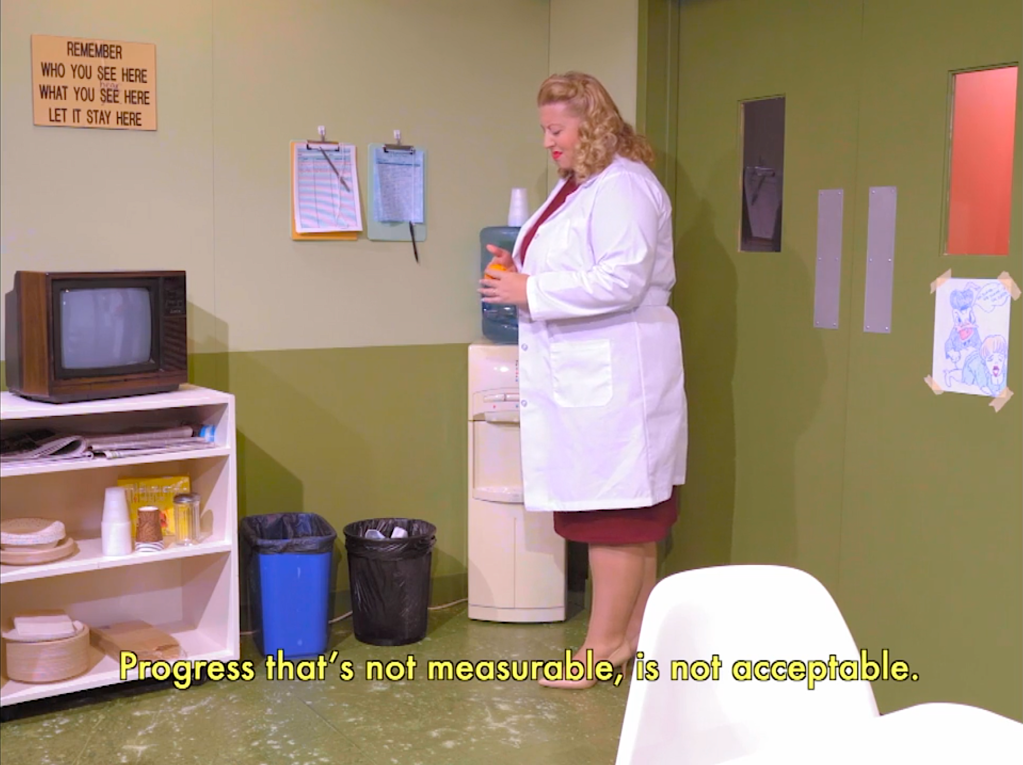

The hospital (featured in episodes 4-7, when we go back in time to the early 90s, before Dawn’s father’s suicide) is rather Kafkaesque (a sign on the wall in the common room reads: “Remember who you see here, what you see here, let it stay here” which is actually an Alcoholics Anonymous slogan but quite unsettling out of context). Dawn’s father and Ed seem to be held there against their will and even plot their escape in episode 7, their main obstacle being that the hospital is run like a business and thus needs to fill the hospital beds (though, paradoxically, it’s Dr. Slade’s obsession with the bottom line, it seems, that inspires her to discharge Mac prematurely, indirectly causing his suicide; Ed hands him an orange as they wheel him out.) In truth, though, the hospital is really yet another American trope, a stand-in for what Joy and all other humanists would say is wrong with America: that any attempt to treat ordinary people humanely (by, say, organizing art therapy classes to heal Vietnam vets who have been traumatized by America’s own senseless war) is bound to get cut sooner than later by someone who is pure evil hiding behind facts and figures (in case you would be inclined to see Dr. Slade as just a person facing difficult decisions about how to run an institution, she spells it out for us in episode 7 with libretto by Jason Cady: “I’m excited to see that art therapist soon and tell her the program’s not renewed… There’s no genius here to be created. Only dangerous subjects to be sedated… I’m overjoyed to fire Joy.”)

(pictured from left: Eliza Bonet, Britt Hewitt)

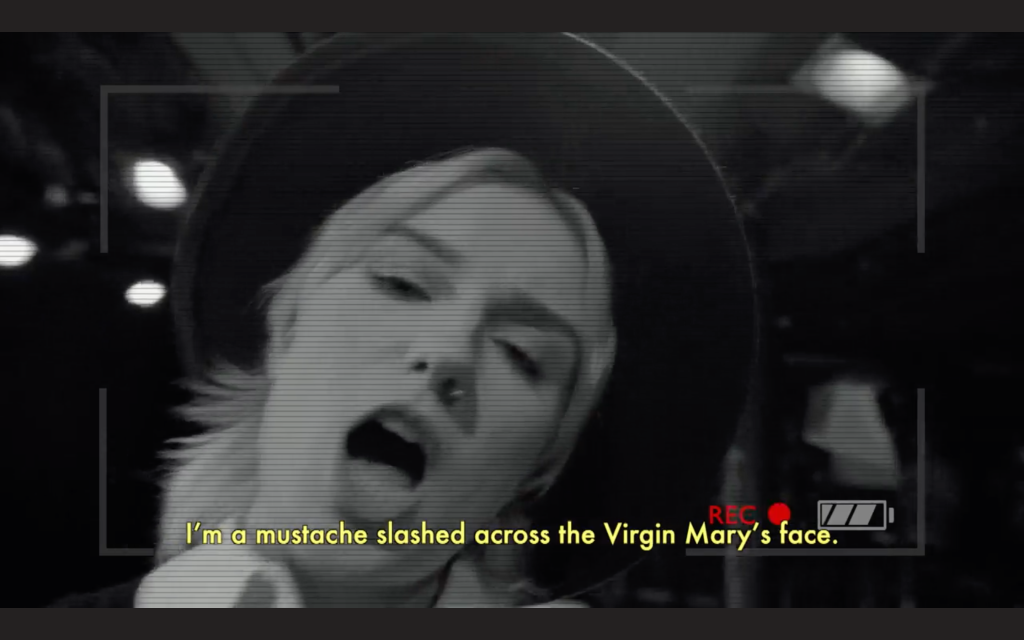

This brings me to the politics of the show, which manage to be palpable and confusing at the same time. One example nearly kept me up at night: When, in episode 2 (libretto by Jerome A. Parker), Dawn excitedly tells Carla about her art history class and how she wishes to create an “anti-rococo” twist on Fragonard’s “The Swing” which would feature an army of women “resistors with masks, Molotov cocktails, graffiti cans, machetes” who would be “armed to destroy the lies” and the two women sing of a “full on revolution” or, before that, when Carla sits in front of Dawn’s father’s painting, confounded, and screams “he’s a man!” implying that being moved by his painting is somehow fundamentally problematic because of his gender – how is this supposed to be understood? Is it supposed to make us sympathise with the characters? Or is it satire? Is it a critique of the anti-man rhetoric which may leave people like Dawn’s father behind? Masculinity is a strange thing in Everything for Dawn. Dawn’s father is stereotypically withdrawn into drinking beer and watching TV. It seems it’s Dawn mother who had him paternalistically checked into an institution, at least judging by Mac’s posthumous reproaches in a duet in episode 3. The only other male character, Ed, is modeled after the literary trope of the madman or the wise fool (though he is more outwardly kooky than Mac he is better at coping emotionally with institutionalization, to the point where I wondered if he’s faking his madness to get by.) Only upon deeper thought did I notice a strange connection with the earlier “feminist revolution” scene: Ed sexualizes Dr. Slade in pictures he draws in art therapy class. He taunts her during her inspection of the art classes: “Now Donald Duck is being fucked by Dr. Slade. And Donald Duck who is me, expressed through the unconscious, is howling out with glee to say ‘I’m healed!’” (episode 5, libretto by Jerry Lieblich.) Shockingly, an actual cartoon drawing of Dr. Slade being taken from behind by Donald Duck appears in episode 7, when Dr. Slade sings about how happy she is to end the art therapy program. Dr. Slade rips the drawing off the wall right after singing “It’s my hospital. I must be fiscally responsible” and the gesture is that of a villain who hates creative expression, yet she is also a woman tearing down an image in which she is being degraded. It’s a crudeness that appears out of place in a work that earlier problematized an image as benign as Fragonard’s “The Swing.” It’s all the more confusing because Ed is a sympathetic character. Madness has often been used in literature to symbolize a kind of transgressive wisdom. What is the transgressive wisdom of Ed’s lewd picture? Is it that it’s okay to menace women sexually as long as those women are in charge? Might this be a case of the impossible moral standard that women in power must live up to – of being nice while holding on to authority? Or does Ed represent the fact that men’s sexual desire for women has become so problematized after #MeToo, that only a madman can express it? Unfortunately, the operatic format simply does not lend itself to the exploration of such nuances; these tonal and moral contradictions left me wishing for a different format for the story, one that would allow the writers to delve more profoundly into the interesting questions they set up.

(pictured: Laura Strickling)

Despite its moments of philosophical headiness (usually concentrated in something like arias or ensembles) the work comes off as an homage to TV shows more than to opera. This is the case even on the granular level of the script, which has a lot of dialogue featuring filler “likes” and “ums” and “mans” and unfinished sentences which sound strange when sung, even as I could imagine them written down on the page as part of a fairly standard TV script (the more heady aria sections, on the other hand, sometimes sound funny when sung and it’s not clear if this is intentional). I did wonder, as I watched, if the oscillation between very intellectual lines, complex moral subjects and over-casual non-libretto-like dialogue, both of which could be approached in TV shows but seem out of place in opera, are a result of the fact that the creators are classically-trained artists of various sorts (composers, instrumentalists, librettists, singers) who have lived their whole lives in a world where those skills were marginal compared to the ubiquity of the TV set which was, in their Gen X and early Millennial childhoods, the hearth of the American home. At least there was a hearth – streaming, by contrast, is a solitary enterprise. Perhaps that’s why this TV opera drips nostalgia.

(picture from left: Aaron Engebreth, Laura Strickling, Joshua Conyers)

The opera world may want to make opera “like the movies” or “like TV” but opera’s strength, from its inception, has been music. At its commercial heights, opera was an odd, frolicking entertainment rather than a narrative art, vibe and spectacle over story. It’s history is also very much that of a communal activity. Before European audiences decided that sitting silently was the only way to enjoy great musical art, opera was as much a social occasion as it was a time to sit and listen. Think jazz, pop or rock concerts more than today’s live opera-going experience or even going to a movie theater. There were periods in opera’s history when it was acceptable to only listen to the arias and chat during recitatives.[4] This raises all sorts of questions about the viability of opera on screen, and particularly on streaming platforms. In any case, if a group of librettists decides to write a TV script they risk writing something like a TV script, which may end up making the music feel like noise you have to sit through as opposed to a presence that enhances the story, or even gives it purpose.

One would predict the more or less uncoordinated contribution of 10 different composers to feel disjointed and pastiche-like but it didn’t. The uniformity was surprising given that the composers had utter freedom with the only, though notable, limitation being the small ensemble (the instrumental ensemble, in fact, had been chosen partially by the producers and partially by circumstance: Maya Bennardo on violin, Hannah Levinson on viola, Tristan Kasten-Krause on double-bass, Matthew Evans on percussion and Karl Larson and Will Healy on piano.) Even though the composers had the option to add any self-produced electronics, only two composers seemed to have actually taken advantage – Jason Cady used a synthesizer in episode 1 and Aaron Siegel seemed to add some helicopter and birdsong sounds in the background of episode 5 (there was actually very little diegetic sound added by the film crew; I can only recall some in episode 8, composed by Clarice Assad, where there are car sounds and the sound of a door buzzer). The relative uniformity of the music may have to do with the fact that Jason Cady, Kamala Sankaram and Aaron Siegel (currently the three directors of Experiments in Opera, who each composed one episode) hand-picked the composers to suit Experiments in Opera’s overall aesthetics.

(pictured from top left: Laura Strickling, Meroë Khalia Adeeb, Joshua Conyers)

If I were to name the musical aesthetics of Everything for Dawn, they seem to be driving rhythms and ostinatos, neo-tonality, influences of jazz and other music deemed non-classical (this is connected to a fairly frequent use of a drum kit for percussion), overall conservative use of instruments and voices, a kind of minimalism that doesn’t like to call itself minimalism, because it isn’t, but is definitely downstream from it. That, too, is a certain kind of Americana. It is nice to see that localized compositional styles still develop; I imagine Everything for Dawn is a capsule of the current sound of the American indie opera circuit. On this circuit, there seems to be an agreement that music should be accessible, and accessibility seems to be achieved through relative consonance and frequent grooving. Perhaps this is also why the composers all chose standard notation, which is to say, mostly writing pitch and rhythm out for everyone at all times (to the point of seeming averse to rubato as well.) This ties in to another uniform decision, which was to not differentiate much between aria and recitative. Recitativo secco went out of vogue a long time ago, but what was lost with it are moments of more natural acting and focus on story over music, which would suit the colloquial dialogue of many of the episodes and particularly suits comedic timing (and also allows the listeners brain to rest a bit). As a singer of contemporary music, one idea I would like to plant in the minds of composers is that there is a rich world of play out there around the union of voice and drama, which gives singer-actors control over some elements of pitch and rhythm (part of what characterized the recitativo secco is letting the singers be led by the rhythm of the words).[5] Allowing singers some leeway in either pitch or rhythm might be a good way to bypass the marionette effect that puts contemporary audiences, used to the most naturalistic of acting, off of opera.

Unfortunately, something is lost in the one-composer-per-episode model because there is no space to develop a musical language for the entire work (forget leitmotifs), as that is a kind of planting and payoff only possible on a larger scale. A canvas of 15-20 minutes is very little to work with for an opera composer. Experiences, of course, are subjective but I can, again, offer a study on a sample of one and say that during Everything for Dawn I rarely experienced that thing one looks for in opera, where the music suspends time so that one savors the moment, unbothered by “what happens next.” I can think of some exceptions, like episode 6, composed by Melissa Dunphy. It was the only episode to use a chorus, here representing the impersonal bureaucracy of the hospital (in a somewhat non-cinematic move sung by three singers who were also soloists: Meroë Khalia Adeeb, Laura Strickling, Joshua Conyers) and I recall two saccharine operatic swells in moments when the characters are saying something banal with a profound subtext (when Dawn is pleading with her father to be able to use the car and when Dawn’s father talks about wet dish towels by way of explaining his aloofness.) I point out these particular compositional decisions not as musical ones but as dramatic ones which happen to use music, and that is the kind of thing I often missed throughout the series. This may simply be a personal preference, but moments when the music describes what’s happening don’t count to me. The listener doesn’t need music to tell them how to feel i.e. cheerful tingly music when the characters are happy, dissonant, jagged music when the characters are angry etc. though I understand there’s a tradition of descriptive music in opera. I wonder if, rather, a kind of contrapuntal thinking shouldn’t be applied to the interplay of text and music – independent lines, avoidance of parallels. When I said I binged Everything for Dawn for the wrong reason, I meant it wasn’t for the union of music and drama but for the plot, that is, “what happens next.” I suppose one could study the kind of contemporary popular entertainment that viewers watch again and again to find out why some pieces keep our attention through plot and others have us coming back to bask in the images and music alone. I would posit that opera simply has to be the latter.

I already mentioned how conservative the use of the voice was in this series; besides standard pitch and rhythm notation, no composer took advantage of extended techniques, which are easier to work with when recording close-range (unless we count Melissa Dunphy’s episode, again, where there is a spoken line, a recited chorus, and a moment when the chorus mimics the open “ah” of a patient sticking their tongue out for a routine exam or a few spoken lines in episode 8 with music by Clarice Assad – some would say these aren’t even true extended techniques but they were as close as anyone got throughout the series). For the most part, the singers simply had the task of taking their training, geared towards reproducing a 400-year-old tradition, and perform it in a context where its core qualities (to project the voice without amplification) are unnecessary. All of the singers acted like TV actors and sang like opera singers as much as it was possible to do those two things at the same time, which is to say admirably. They were also all very well-cast for their roles. In times past, audiences would have gone to hear them in theaters in order to admire their voices, which may have seemed, in the height of bel canto showoffiness, as awe-inspiring as fast-cut CGI space battles do today. In Everything for Dawn, the singers’ voices are utilitarian – vessels (imperfect ones, because subtitles are at times necessary) for the words, there only because, well, let’s remember it’s supposed to be an opera. When it comes to the acoustical magic-trick of placing pre-recorded classical singers and instruments onto the screen without perceivably warping the rules of space, I appreciate the work of the recording team, music director David Bloom and sound engineer Jeff Cook, as well as the singers for their lip-synching abilities.

(from left: Britt Hewitt, Sishel Claverie, Eliza Bonet, Maggie Finnegan, Meroë Khalia Adeeb)

A lot of the nostalgia of Everything for Dawn lies in the production design, which is also responsible for a lot of those memorable details – changing from 4:3 aspect ratio to 16:9 depending on the time of the action, retro spaces which walk the line between aesthetic and sit-com utilitarian, TVs placed in many of the environments, the meta-intros of each episode which have us Zoom in to TVs from the given time in which the action unfolds, an entire episode (episode 8) shot as a reality TV show (though that may have been written into the script), or, after an entire episode filmed in one shot from the perspective of a painting (episode 9, which unfortunately contained some blocking issues in the one-shot format, because there may not have been enough time to rehearse), zooming out onto the back of the painting, teasing the fact that we can’t see it. It’s interesting to note that the production team, most notably the director Alison Moritz, assistant director Ian Silverman, production designer Jean Kim and lighting designers Stacey Boggs and Betsy Chester, have much more experience in theater than in film. In fact, looking from the outside, the film crew was really a theater crew with one primary film advisor, director of photography Eric Thomas Paton, and a film editor, Travis Ford. It was this team, however, that created a lot of the charm of Everything for Dawn. The fact that the lighting was at times blatantly theatrical as opposed to cinematic ended up being interesting rather than tacky. However, I think that in the next such opera-on-screen experiment, there should be more involvement by film experts, just to see what would happen.

Perhaps too predictably, I kept thinking of Marshall McLuhan as I watched Everything for Dawn but it wasn’t clear to me which was true, here: Opera is the message. TV is the message. Streaming is the message.

What Experiments in Opera has done with Everything for Dawn, in any case, is remarkable in ways that may not be at first apparent. It is a work of conceptual art as much as (or even more) than an opera or a TV show. It is conceptual art about the death of opera in a world of streaming by an indie opera company, itself in opposition to the mainstream opera business. It is also about money, which is why money (trying to make ends meet, art funding, selling art, even perhaps the symbolism of Donald Duck) is such a big theme of the story. The ability to fund a project like Everything for Dawn is a strategical feat, one that leans on the fact that there’s strength in numbers: To an art-funding committee supporting 10 composers and 6 librettists in one shot is a nice deal. The tragedy would be if Everything for Dawn was the pinnacle of this hybrid indie-opera-company-creates-serialized-show-for-a-streaming-platform genre, for the very reasons that loom over the themes of the show. The last episode leaves room for the story to continue, an open hand, palm up, extended to anyone who wishes to fund the continuation of an experiment which has only yielded preliminary results. I am not convinced that opera belongs on streaming platforms because I think it has the most value when enjoyed communally and without the possibility of clicking away, but I don’t want to live in a world where no one ever experiments with the limits of a medium. Artistic experiments with uncertain returns are the only way an artistic scene can thrive and I’m thankful to Experiments in Opera for proving it’s possible to be ambitious about funding such experiments.

| Ema Katrovas (CZ/US) is a classical singer, currently working on an Artist Diploma at the Espace Transversale de Création at the CNSMD in Lyon. She runs a podcast called Artists on the Verge, and has published translations into English of the works of Pavel Šrut and Bohumil Hrabal. |

[1] For an interesting look into the differences between TV and streaming platforms, and how the way TV “played to the middle” of the American viewership, while it did clamp down on creative freedom, had the advantage of bringing people from across the political spectrum together over contentious topics, I recommend the episode “When Will Met Grace” from Malcom Gladwell’s Revisionist History podcast.

[2] I was able to ask some questions about the process through a brief email correspondence with Jason Cady, one of the founders of Experiments in Opera. Any knowledge I have of the process comes from my interpretation of that correspondence.

[3] Episode one was written by Jason Cady though it’s unclear how much of the actual plot points can be attributed to a single librettist. In this review I only credit direct quotes to particular librettists, not plot points.

[4] I am not a histories but I learned a lot about the broader social context of opera (how it was consumed, who attended it, and who funded it throughout its history) from Daniel Snowman’s book The Gilded Stage: A Social History of Opera and recommend it to anyone interested in an introduction to that subject.

[5] Off the top of my head, from my own repertoire, I think of George Aperghis, who is often precise in rhythm but oscillates between precisely and approximately notated pitches and vocal sounds, or, on the other end, Aribert Reimann’s dramatic setting of Plath’s “Lady Lazarus” which has precise pitch notation but approximate rhythm.

Leave a comment