by Ema Katrovas

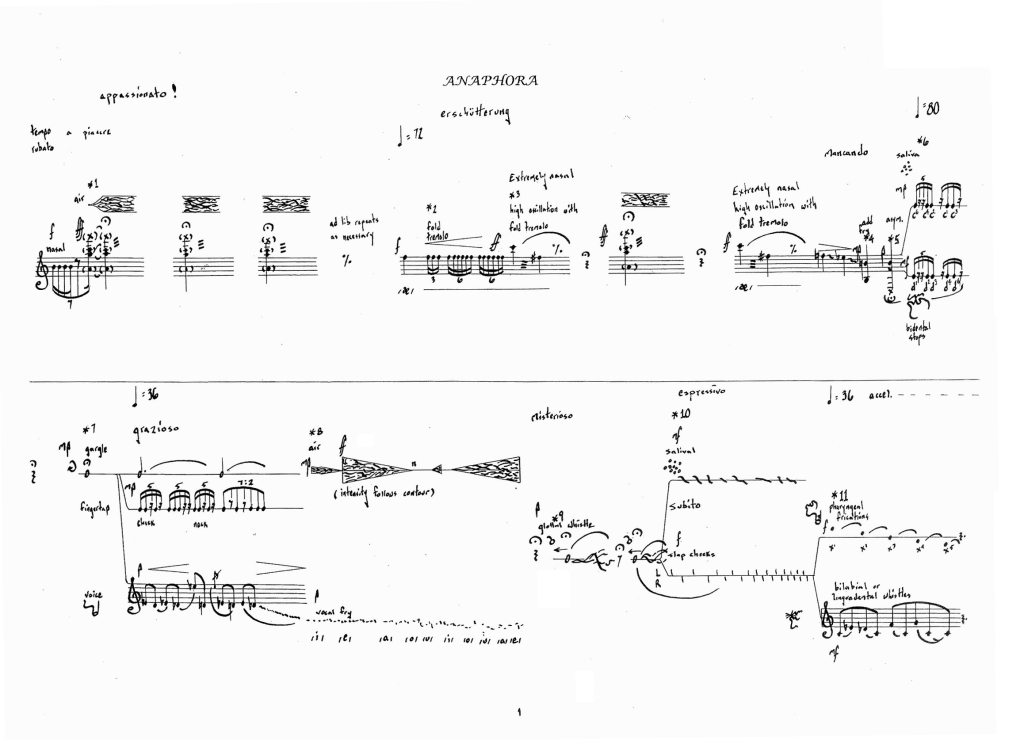

ANAPHORA

For solo voice

Composed by Michael Edward Edgerton

Premiered by Rebekka Uhlig at the Festival Speicher V (Berlin), 2001

Published by Babel ScoresYou can listen to an audio version of article on the author’s podcast here.

“Is communication something made clear?

What is communication?

Music, what does it communicate?

Is what’s clear to me clear to you?

Is music just sounds?

Then what does it communicate?”

John Cage, “Communication,”

lecture-performance given at Darmstadt in 1958

“The big explosion,” mezzo-soprano Cathy Berberian recalled,[1] came in 1958: sobs, sighs, tongue snaps, screams, groans, laughter, coughs, hums, recitation, jazz licks and folk songs. It was the same year that John Cage shook academic music with his series of lecture-performances at Darmstadt, the same year he and Berberian collaborated on creating Aria, the work that, according to that very Muse of Darmstadt, Berberian herself, started the “explosion” aimed at blasting open the constraints of lyric singing. In 1966, armed with about a decade of making sounds deemed “obscene” by old ladies attending matinées[2], Berberian published her manifesto on what she called “the new vocality” which began with the question: “What is this new vocality that appears so threatening to the old guard?” Surely, that was the end of the old guard.

Cut to 2012, and composer and vocal researcher Michael Edgerton laments, with a little sigh[3]: “All the other instruments are [experimenting], just not voice.“ So, what happened? In the introduction to the first edition of his book The 21st Century Voice: Contemporary and Traditional Extra-Normal Voice (2004) Edgerton explains: The era of vocal experimentation came to a “screeching end” sometime in the late 1970s and, according to Edgerton, this was because a lack of scientific understanding of the voice by composers, and a lack of systematizing of the sounds the voice can make based on how it makes them, rendered vocal experimentation a series of “nonscalable novelties.”[4]

Anaphora (2001) is a composition Edgerton himself uses as an example of his inquiry into the limits of the human voice. It is somewhere between art and science experiment. It is testament to its important place in the version of vocal music history I am painting, here, that I know about and ponder the existence of Anaphora, despite never having had the opportunity to hear it live.[5] It is also worth noting that, like anyone who is interested in the human voice as a contemporary musical instrument, I own a copy of Edgerton’s 21st Century Voice simply because it is the only catalogue of its kind and comes up in any conversation I have ever had about resources for singers wishing to explore so-called “extended techniques.” Edgerton has certainly made his mark in this very specific corner of the arts.

Anaphora consists of 56 classes of vocal multiphonics. In the most layman terms possible, multiphonics are “more than one sound at once.” Vocal multiphonics can be as simple as lip trilling while humming (something many singers use daily as a vocal warm-up) to something as terrifying as asymmetrical vocal fold vibrations and as elusive as a breathy glottal whistle. Only four singers seemed to have accomplished this 20-minute feat: three listed on Edgerton’s website, Rebekka Uhlig, to whom the work is dedicated, Angela Rademacher-Wingerath and Almut Kühne and a fourth, Felicita Brusoni, currently doing her doctoral research into the “extra-normal voice” under Edgerton’s tutelage.

The title of the work refers to the rhetorical device of repetition. The score begins with a passage from Shakespeare’s Richard II:[6]

This royal throne of kings, this sceptered isle,

This earth of majesty, this seat of Mars,

This other Eden, demi-paradise,

This fortress built by Nature for herself…

The quote goes on for another 12 lines, followed by the composer’s note: “And thus the puzzle is presented. In an unaccompanied solo for voice with no text, can the observer find the relation between Shakespeare and here?” I’m not sure what this quote in particular has to do with Anaphora other than the employment of anaphora, except maybe that both the quote and the composition could be reduced via a faux-Schenkerian analysis to: This this this this this this this this.

Anaphora is arranged in such a way as for two adjacent multiphonics to share an element of their production. That is the through-line. It is a through-line indiscernible to the ear of anyone who is not either the composer or someone who has learned to perform the piece. The struggle involved in producing each sound is intended as part of the experience of the piece and this necessitates frequent pauses between different multiphonics. The composition is only sonically coherent if one thinks of it as a catalogue, a kind of vocal bestiary, a series of examples (this this this this this). As I listen to Anaphora, I am overwhelmed by questions which, once I get past the first layer (“Why am I listening to this? How much longer does this last? Do I have to finish listening to this?”) get more interesting:

- Can a vocal sound that you would never hear a human make in real life be expressive?

- If the only time you would hear a human make a certain sound were in distress or in illness – is it expressive then? And does it then only express distress and illness?

- Why is the word “expressive” so often thrown around vocal music, anyway, as if “to express” were an intransitive verb? Expressive of what?!

- Is the fact that the singer’s struggle to produce these sounds is intended as part of the piece a theatrical or anti-theatrical device?

- If a vocal noise itself is so unusual as to evoke nothing beyond itself (not even a pitch) is it at once a thing and a representation of a thing? Is this Duchampian, then? Is each uncommon vocal noise within this piece a signifier and a signified at once?

- Why do I not ask myself this same question when listening to other types of music which consist of non-musical noises, like some musique concrète? Does the process of sampling add a layer of artifice which somehow makes each noise a representation and not simply the thing itself?

- Why do I not ask myself this same question when listening to other types of abstract music? Is abstract music also not both the thing and the thing it represents? Does using a pitch system change anything? Since that system recontextualizes each pitch such that it plays a role within a system, does that render each pitch a symbol and is that what alleviates this feeling I have that I am not regarding a piece of art but listening to a series of scientific examples?

- Why do I not ask myself this question when listening to compositions for musical instruments which employ extended techniques, ones which also so often deconstruct the sound of the instrument to the level of noise? Is it simply the fact that the voice is first and foremost a biological structure?

- Is everything that is unfamiliar also incomprehensible?

- Is everything that is unfamiliar also disturbing?

- Is everything that is incomprehensible boring?

- Why is there such an overlap between that which is unfamiliar and that which is disturbing and why does that so often, in the context of experimental art, manage to be boring?

- If most people observing this composition do not understand the physiological processes taking place, is this piece still communicating with them?

- What does it communicate?

- What does it mean to understand this piece?

- Is the fact that a composition might make me research a new subject in order to better understand the composition mean that it is communicating with me? Or is it not communicating at all and, in not communicating, forcing me to answer a question myself?

- Is that cheating? Am I cheating or is the composer cheating?

Anaphora, at its best, is a study of texture, a training in hearing multiple sounds at once where before you may have heard just a screech or a gargle. In some sense, it carries on the great tradition of musical etudes. This etude, however, does not put on display the musical possibilities of an instrument or tuning system but the physical possibilities of a biological structure. The actual experience of listening to Anaphora is therefore not an aesthetic one, like listening to Chopin études but, rather, (often morbidly) fascinating like going to a natural history museum.

In the preface to the first edition of The 21st Century Voice, John Cage is conspicuously absent from Edgerton’s list of composers experimenting since the late 1950s with “non-standard vocal music.” In the version of vocal history I am painting, however, the juxtaposition of Cage and Edgerton is particularly poignant. Cage wanted to explode the European “classical” music laboratory with questions it was not built to answer. Edgerton wants to reconstruct the laboratory, this time not in the image of the outdated European notions of “beauty” and “masterpieces” (which John Cage made a career of criticizing) but, rather, on scientific cataloging and testing. If the point of Cage wasn’t to answer questions but to ask them (“I have nothing to say and I’m saying it”), the point of Edgerton isn’t to communicate but to demonstrate (This this this this this.) Cage’s Aria can be sung by anyone, regardless of vocal or musical training. Anaphora has only been accomplished by four singers, under the composer’s tutelage. The sobs, sighs, laughs or coughs which Cathy Berberian referred to as “the big explosion” were universally-recognizable vocal sounds which were naturally expressive precisely because they appeared in real life. The sounds proposed by Edgerton are unlearnable to all but a few who wish to spend a good portion of life learning them (and I would argue some, like the glottal whistle, are not universally trainable) and undiscernible to most listeners, because they are outside of the sounds most humans make or distinguish. This is an example of the natural progression of any discipline towards virtuosity. Anaphora owes its existence, in part, to Cage who was intent on exploding the notion of what musical sound can be and Anaphora may be as far as one can go within vocal music in response to some of those questions Cage posed back in 1958 (“Is a truck passing by music?” etc[7]).

Anaphora is not the answer to the problem of experimental vocal music as a series of “nonscalable novelties,” quite the opposite. However, just like scientific inquiry slogs through the tedious trial-and-error involved in inventing things we take for granted, Edgerton’s experimental vocal compositions, Anaphora among them, do the grunt work future vocal artists can refer back to whilst saying something beyond this this this.

In 2014, in the preface to the second edition of The 21st Century Voice, Edgerton is more optimistic about the future of vocal experimentation: A “fragmented cultural economy and the decline of importance of massive score and recording publishers,” he writes, have inspired “large segments of artists to push boundaries in ways that resemble times past” with the idea not of selling “to the masses or even to the small market of classical music consumers but simply to continue that time-mandated inquiry into ‘What’s next?’” In conversation with Felicita Brusoni,[8] the singer doing doctoral research under Edgerton’s tutelage, I found she, like I, is concerned with the communicative possibilities of the more difficult and bizarre “extra-normal” vocal sounds she has labored to master. Brusoni, like most experimental artists of our generation, thinks about accessibility and talks about “involving audiences more” in her performances. It makes me think again of the Muse of Darmstadt, Cathy Berberian, who, later in her career, turned away from the experimental realm she inspired, to sing parodies of Beatles songs and banter in campy costumes between nostalgic salon music sets in something as close to popular music as the “Western classical” tradition has to offer. We seem to always be swinging this way and that between experimentation and what we might call communication. Artistic experimentation might be to communication as science is to technology: the former a highly-specialized process executed in secluded laboratories, the latter something more pragmatic and broadly shared. It is interesting to consider that it is through technology that scientific knowledge changes the way we live and thus attains broader historical implications. The question, then, is what form of communication we will invent using our legacy of vocal experimentation, what technology we will invent with the science we already have.

| Ema Katrovas (CZ/US) is a classical singer, currently working on an Artist Diploma at the Espace Transversale de Création at the CNSMD in Lyon. She runs a podcast called Artists on the Verge, and has published translations into English of the works of Pavel Šrut and Bohumil Hrabal. |

[1] 1979 interview with Cathy Berberian for the KSO conducted by Frans van Rossum: https://soundcloud.com/cberio/cathy-kro-short-a

[2] Ibid.

[3] Stimmig, 2012 documentary by Lena Giovanazzi and Daniel Büche: https://vimeo.com/54681834

[4] The fact that I am not entirely sure whether I understand what Edgerton means, here, is interesting in and of itself given that so much of my reflection on his composition has to do with communication. Here is the passage I’m quoting from:

“Because of the lack of standardized fingering charts for vocal sounds production within the larynx, most composers attempted to explore performance technique and expression through phonetically based articulatory procedures or, to a far lesser degree, through the combination of multiple vocal sound sources, combining primarily harmonic and inharmonic input, or less with special phenomenon, such as subharmonics or overtone singing. For many, these results were thrilling and fine, but as such, they often resembled a series of nonscalable novelties that often found little perceptual density necessary to experience the multiple layers during repeated hearing of interesting work. As a result, the era of extended vocal techniques came to a screeching end sometime during the 1970s or so.

Today, in the early twenty-first century, this book proposes to lay out the structural foundations that underlay decoupled and scaled multidimensional phase spaces for voice. It is this author’s contention that continued artistic exploration could be achieved by decoupling select robust parameters involved in the production of sound… For performers, this may mean having to relearn their instruments.”

[5] I have listened to all the recordings available online. I do think hearing a mere recording greatly impoverishes the experience of this piece, given that so much of it is about subtle differences in texture – I try to adjust for that as best I can in my reaction.

[6] I only know about this quotation in the score thanks to a conversation with Michael Edgerton and Felicita Brusoni about the work available here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uERfiufCNPk

[7] From John Cage’s lecture-performance Communication.

[8] You can listen to my profile of singer Felicita Brusoni and her work in “extra normal” voice on the Artists on the Verge podcast: https://spotifyanchor-web.app.link/e/sjLx8En0gvb

Leave a comment